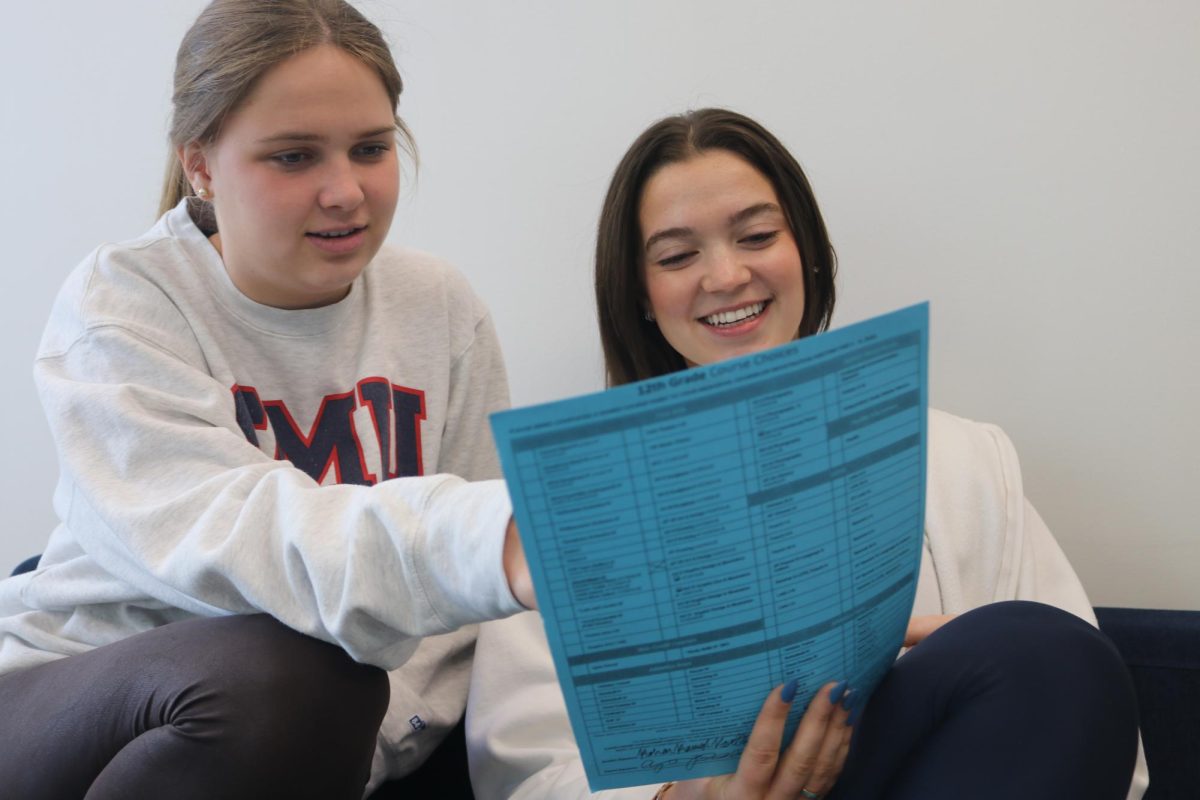

Looking upon stacks of bright colored sheets whose markings decide what courses students will take the following year, counselors are left in a precarious spot tasked with deciding which academic programs will return for the 2025-2026 school year.

In hopes of maximizing teachers’ time, cutting costs, and making way for the devolving interests, the district is looking to dismantle or alter academic programs that have been consistently shrinking in recent years. The rising popularity of the MAPS program, coupled with increasing stress placed on students’ grade point average (GPA), has led many to steer away from personal interests in favor of a spot in the top 10th percent of their class.

“Luckily, I am in the top 10 percent of my class, but I’m also in yearbook and Belles, and both of those are regular classes,” senior Katherine Ditchman said. “It’s almost like I’m punished for being involved because they lower my GPA so much over time.”

Choosing to participate in an elective course weighted on a 4.00 or 4.50 scale as opposed to an AP course weighed on a 5.00 scale automatically sets students behind their peers, often not accounting for the massive amount of work one must take on both in and out of the classroom as a member of a student-run organization.

“I get like zero sleep as is, trying to maintain the grades I do in order to balance out my regular classes,” Ditchman said.

The Highland Park School District follows a 5.00 GPA scale, meaning they take into account the difficulty of each course, adjusting the student’s average accordingly. They take into consideration the amount of advanced placement or honors classes one takes and add on anywhere from five to ten percent of one’s final grade depending on the course.

“There are schools just like Highland Park that are on a 100-point scale meaning they take your actual grade,” academic intervention and support teacher Charles Trahan said. “It doesn’t make a difference if you’re going to a school that has a 5.0 versus a 4.0 scale because it will all average out.”

Not knowing that colleges will take a raw score as opposed to a weighted one, many students will hyper-fixate on their GPA, viewing it as a one-way ticket to their dream school.

“You think about schools that are getting over 50,000 applicants, at some point, there has to be some type of system to narrow it down,” Trahan said.

With that many applicants to sift through, admissions officers must consider GPA to make initial selections. In reality, the admissions process is much more nuanced as schools don’t solely focus on that all-important number, hoping to see a well-rounded and driven student with some real-world experience outside the classroom.

“It’s hard for kids who are super academic because they’ll drop the class junior or senior year, and those are the kids that have already been trained in journalism,” Ditchman said. “Instead, they are going to either MAPS or taking AP classes because they think that’ll help their resume more.”

Pressures to have the highest GPA or the longest resume among one’s peers or as a result of parental pressures can lead students to go to extremes and go against moral judgments in search of an unattainable goal.

“There is quite a lot of GPA pressure to the point where students who usually would be super honest and have integrity would go to the point of cheating,” Ditchman said.

While external pressures from both parents and teachers may lead students to bend their morals in favor of a higher grade, that pressure can also be adjusted to help empower students to reach their full academic potential.

“We have a lot of different ways to make students think realistically about their future, but then also parents can tell or encourage their students to challenge themselves when a student may be hesitant,” Trahan said.

Looking to work around GPA restrictions and a lack of student engagement, elective directors are changing course requirements in hopes of attracting more individuals interested in their courses.

“Normally it’s just like an open audition for anyone, but we’re looking at changing some of the prerequisite requirements because the enrollment is not conducive to us growing a department for the future,” Theater director Brittany Murphy said.

However, adjusting admittance standards might not be enough to make up for the lack of interest facing smaller elective programs. With many of these programs, like the middle school journalism class, having already been replaced at the middle school, teachers are left without a group of rising freshmen that would automatically enroll in their course.

“In the past two years there have been two new teachers at the middle school,” Murphy said. “I think a lot of people who were in middle school theater may have stepped back and found other things to be a part of.”

Factors both in and out of the district control have contributed to this massive drop in elective enrollment in recent years, leaving the most vulnerable programs susceptible to

“Because we are generally high achieving, it makes an exceptional student not seem quite as exceptional on paper if they choose to pursue their passions,” Trahan said. “It’s a really hard pill to swallow when trying to help students grow holistically.”