When New York Times bestselling author Mark Sullivan woke up on his 30th birthday, he immediately knew that something was wrong. Ever since childhood, Sullivan had dreamed of becoming an author, and on that day, he realized that he needed to pursue that dream, instead of the reporting career he had dedicated the previous decades to.

“I knew I wanted to be a novelist and magazine writer and all this stuff that wasn’t just daily news journalism,” Sullivan said. “But it wasn’t until the morning I turned 30 that it really hit me that I wasn’t attempting it. I told my wife, and she just said, ‘okay, if that’s what you want to do, you have to get up early and put in the work.’”

Pursuing his career as an author became a second job to Sullivan, who would wake up at five o’ clock in the morning and write for two hours before going to work for sixty hours a week as a reporter for the San Diego Tribune. Eventually, though, Sullivan quit his job and pursued writing full time.

“Writing became a discipline,” Sullivan said. “Once I quit and I was working on my novel full time, I would always try to write at least a thousand or two thousand words a day. Those words, they really add up. You know, you write a thousand words a day, and in a hundred days you have a draft with a hundred thousand words on it.”

Sullivan’s first book, “The Fall Line,” a thriller novel, was published in 1994 and later named a New York Times Notable Book of the year. Despite the success of this book and the others that followed it, Sullivan found himself distraught. He was in severe financial trouble, straining his relationship with his wife, and his brother had recently passed as a result of complications from alcoholism.

“My brother was smart,” Sullivan said. “He was the most well-read person I’ve ever known. Creative, too. Just a tragic figure.”

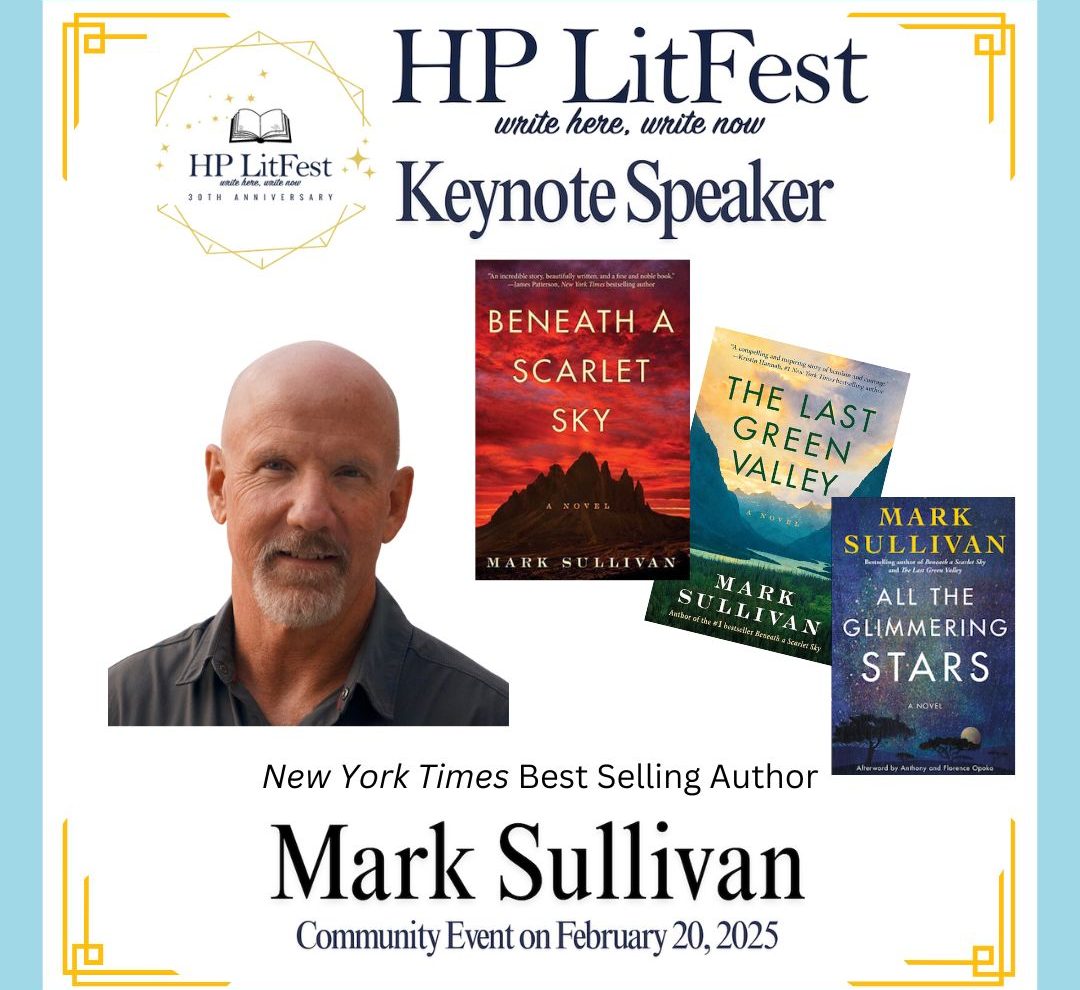

During this time, Sullivan attended a dinner party, where he first heard the story of the little-known war hero Pino Lella, and where he first felt the calling to write historical fiction, which manifested in Sullivan’s 16th book, “Beneath the Scarlet Sky.” Later, Sullivan would fly out to Italy and interview Lella in person, learning the stories of Lella’s teenage years, spent running an underground railroad that helped Jews escape the Holocaust by smuggling them through the Italian Alps.

“[Lella] was a happy-go-lucky guy,” Sullivan said. “As I talked to him, I found out just how difficult a time he had in the war. His philosophy, when I heard it all of a sudden, the death of my brother started to fade. But I could not have written “Beneath the Scarlet Sky” if my brother hadn’t died. I wouldn’t have understood grief and tragedy the way I did. And I was able to write about grief and tragedy in the book in a realistic way because I had lived it.”

Sullivan’s pursuit of historical fiction has taken him all over the world. For his 2024 novel, “All the Glimmering Stars,” which chronicled the lives of two child soldiers escaping the fanatical Lord’s Resistance Army in Uganda, Sullivan visited the city of Gulu in northern Uganda, where the book’s two main characters’ real life counterparts met for the first time.

“We went everywhere we could in northern Uganda,” Sullivan said. “That was part of the story. We wanted to go into Sudan, but Sudan’s really messed up right now. And my wife, about eight years ago, made me promise I wouldn’t go into any more conflict zones.”

In his presentation, Sullivan discussed the difference between the act of storytelling, which entails the crafting of a story with a beginning, middle, and end, and writing, which is the simple act of putting a pen to paper, and how a synthesis of the two into a novel can possess the ability to permanently alter the lives of the people who read it.

“To me, a book is a success if I get letters telling me that I have changed people’s lives,” Sullivan said. “That’s what I’m after. I’m after the impact of that.”