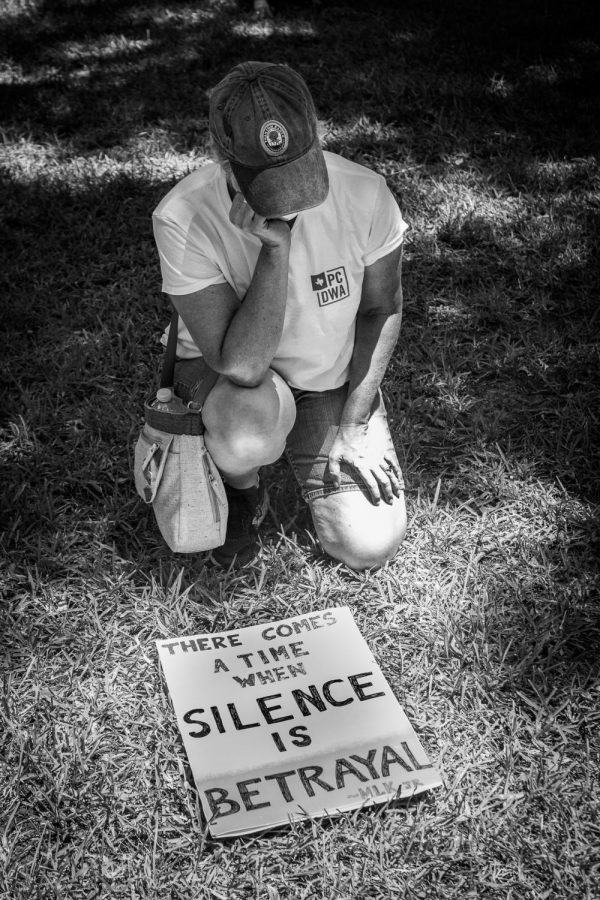

A high school parent kneels with her sign during an 8 minute moment of silence in honor of George Floyd. When Floyd’s death sparked nationwide protests in honor of the Black Lives Matter movement, Park Cities residents held local events. Shortly after, a group of students crafted a video titled “Dear Highland Park” to raise awareness of racial issues in the school district.

The History Of Race In Dallas: Highland Park’s Past, Present And Future

High school works to create positive culture of inclusion in 21st century after past of segregation

“I said, ‘So, it’s a separate school system, in the middle of this other school system?’ It was unreal to me. People in Dallas are just used to this now. But to an outsider, I just saw this map and realized the unbelievable segregation that exists within the system.” – Mike Koprowski, The Single Biggest Problem in Dallas, D Magazine, 2018

Abbott Park has all the amenities one could expect from a public park in Highland Park.

There’s a tennis court and a shaded playground to save children from the hot Texas sun.

Better yet, the park has convenient access to the Katy Trail.

But in 1971, it wasn’t just a neighborhood park. Instead, it was a publicity stunt.

A Black activist named Curtis Gaines Jr. bought a house at that location from Mary Jo Vines, a white woman supporting his cause. He publicized his intention to move a Black family receiving welfare to the house in order to push the limits of the predominantly white Highland Park community.

That never happened. Gaines’ organization Grassroots Inc. sold the house to realtors. In 1973, the town bought the land for use as a park.

It takes a dive into history to fully understand why Gaines’ threat would have caused ruckus.

A History of Segregation

When Highland Park incorporated in 1915, Jim Crow was in full swing. It was less than 20 years after the Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court decision that enshrined “separate but equal” into law.

In Dallas, implementation of this emphasized the separation part of that ruling. Highland Park was no exception.

In fact, what set Highland Park apart from Dallas was they didn’t need to set up separate institutions for Black and white residents to uphold segregation. There were no Black homeowners in Highland Park at this time.

In his book “Sundown Towns,” James W. Loewen refers to Highland Park as a sundown town, a place in which it was historically unsafe to be Black. According to the companion online Sundown Towns database from Loewen at Tougaloo College, all homes in Highland Park had racially restrictive covenants applied to them in 1913. These covenants forbade the sale of houses to minority populations. The use of such restrictions became illegal in 1948.

The few Black people who did live in Highland Park were live-in maids. To avoid educating Black school-age children in the Park Cities, HPISD paid Dallas ISD to bus them to all-Black Booker T. Washington High School and B.F. Darrell Grade School up until 1961. Carrollton and Irving school districts followed the same practice.

In the year 1950, 50 Black students lived in Highland Park. That number became zero in 1969 when Highland Park residents started voluntarily following a city rule banning kitchens in quarters for live-in domestic servants, according to a 1971 Dallas Morning News article. The rule had existed since 1929.

In 1956, three out of five candidates for the Highland Park Board of Education were entirely opposed to integrating HPISD schools. One candidate, Helen Hilseweck, said it was an issue they could address later when it became necessary.

“It is not yet a problem in our district,” she said to the Dallas Morning News.

A challenge to HPISD’s homogeneity came in 1971. The Black plaintiffs of the federal court case Tasby v. Estes sought to desegregate Dallas schools and filed to include HPISD in the desegregation plan for DISD, claiming it was unfair to have a separate all-white school system in the middle of Dallas. This move ultimately failed in court because HPISD did not have a “significant segregative effect” on DISD, according to judge William M. Taylor.

So, the Park Cities were left to their own devices on desegregation.

By law, they could no longer exclude Black students from their schools, but forcible integration like in DISD simply did not happen. HPISD was an all-white district.

Like Hilseweck said, it wasn’t an issue yet. There was no dual school system for Black and white students because due to a history of deliberate segregation, there were no Black students. In 1975, HPISD became the last school district in Dallas county to integrate.

Moving Forward After Integration

Though HPISD now accepts students of all races, it remains overwhelmingly white. The first Black student, James Lockhart, came to the high school in 1974 and graduated in 1975.

Lockhart appeared in a video named “Dear Highland Park” last year, made by students trying to raise awareness on race issues within the high school.

“Highland Park was an experience,” Lockhart said in the video. “It was new to me. I experienced some things I’ve never experienced before, and I’m quite sure that many of the students at Highland Park experienced some things from me.”

He said he was grateful to have gone to the high school and offered words of encouragement to viewers.

“Success only belongs to you as long as you hold your head up high,” he said. “Smile. Words never hurt you.”

Another alum, Charity McIntyre, is both Black and white and attended the high school from 1988 to 1992. She also attended the middle school in eighth grade.

McIntyre said during the entirety of her high school years, she was the only Black student.

“I don’t identify with one race or the other,” McIntyre said. “I consider myself as both. Going into the high school, I was just ‘that Black girl.’ It was a little different. Some people didn’t care, some people did. I ran into some racial issues with some of the kids, and some I didn’t.”

She also had positive and negative experiences with teachers. In some situations, her mother had to step in.

However, McIntyre describes her time there as mostly good. She did basketball and choir and made friends with students from all sorts of social groups and activities.

Sometimes, she would feel like more of an oddity when she left Highland Park than when she was there.

“They would say, ‘Oh, where do you go to school,’ and you would say ‘Highland Park,’ and they’re like, ‘What,’” McIntyre said.

Mcintyre still keeps up with some of her old classmates on Facebook and even people she wasn’t friends with in high school, chatting and meeting up with them periodically. She also got messages from people apologizing for the way they treated her in high school.

“[They were] saying, ‘I’m really sorry for the way that I treated you in high school. I was just dumb, I was ignorant, I was acting the way other people acted. I was acting the way my parents were teaching me.’“ McIntyre said.

The messages were a shock to McIntyre.

“It blew my mind,” McIntyre said. “I was telling my husband. I was like, ‘I am really floored.’”

McIntyre said if she could go back in time, she would go to HPHS all over again.

She pushes back against the negative perceptions she hears of the district.

“A lot of people just thought ‘Oh, everybody at Highland Park, they’re white, they’re racist, they’re just no good,” McIntyre said. “I had to kind of shut that down. Because they’re not. Yeah, you’re going to find people that are like that. But you can find people like that everywhere.”

Principal Jeremy Gilbert said he heard some parents who are racial minorities say they have always felt accepted in the district. But he’s heard other things from parents too, like wishing for a more diverse faculty that is representative of their backgrounds.

From Black students and other students of color, Gilbert hears that white students don’t necessarily know how to ask appropriate questions or approach conversations.

“Perhaps students that go to schools that are more diverse, they kind of naturally learn that,” Gilbert said.

Gilbert said that there are many areas in which his school is the best, and he’d like to see cultural awareness be one of those.

“In general, students and parents have expressed to me that they love the educational experience that they get in Highland Park ISD,” he said. “They love the opportunities that their kids have. They just want more in regards to cultural and diversity awareness.”

To make the high school a more inclusive environment, Gilbert wants to partner with student clubs to create inclusion initiatives and is participating in Project Unity’s Together We Dine. He points to the Student Council’s annual Race to End Racism event as another way the school carries out that goal.

Gilbert has partnered with about 20 to 25 other schools and their principals, school board members and other school leaders to try to put together a new program.

“Students from Highland Park High School will be able to interact with students from other schools and have critical conversations about diversity and about race,” Gilbert said.

He said the project might start small, but eventually, anyone in the school would be able to participate.

Gilbert said he values climate and culture as a principal. He wants to make sure all students know they are loved, and all students can get involved in something at the school that makes them proud to be a Scot.

“Whether it’s our literature, whether it’s our math instruction, whether it’s our science program, whether it’s our diversity and inclusion awareness, all those areas we can get better in,” Gilbert said. “I appreciate students who have the passion because it’s with that passion, as long as it’s a positive partnership, we’re going to make Highland Park High School a better place.”